Black Seamen in the Georgian Navy & The Age of Revolution

We hear a lot about the Victorian Navy & their abolitionist role, but much less is discussed of the Georgian institution & the presence of skilled black Seamen during the marine age of sail.

Meritocracy and Maritime Employment

As discussed in previous substacks, the Royal Navy loomed large in the 18th century Caribbean not least of all because the Islands became the main theatre of war, which necessitated a constant military presence of the navy, so much so that when white plantation owners in the colonies petitioned the crown and parliament for the defence of the territories they made it clear that reliance on the navy was crucial for protection. Royal Navy Historian Margarette Lincoln, has written of an eighteenth-century naval tradition associated with prosperity & “the defence of Liberty” in contradiction to its policies & beliefs in this time period. In the 18th century the principal role of the royal navy in the Caribbean was to protect the system of chattel slavery in the British colonies, the interests of the white planters’ on the islands and British commercial shipping carrying goods produced from enslaved labour and African slaves as cargo. Historian Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy has pointed out in his book An empire divided “the white colonists, regarded the navy, not the army, as ‘the only efficient protection’ against a foreign enemy” and that the navy was “the first and principal security of the islands in general”. Even when the American war of independence went badly for Britain the royal navy could be relied upon to deliver a decisive Caribbean victory like in the Battle of the Saintes in 1782 against the French, which helped secure Jamaica. There were two main naval stations in Jamaica and Leeward, during peace time and war. In 1782, with a personnel of 30,000 officers (mostly white British), 34% of all the navy’s ships of the line were stationed in the West Indies along with a quarter of all naval cruisers and frigates. during Peace time about 9% of the white population in Jamaica were seamen of the navy in contrast to revolutionary and napoleonic war time when according to the white plantation owner and historian - Edward Long, the navy added 40% to the local white population on the island. The leeward station had similar figures. In 1774 Antigua, the home station of the fleet, “the whites were 1,590, and the negroes 37,808” as mentioned by Author Robert Montgomery Martin based on the estimations of Abbe Raynal. Desertion and disease discouraged naval captains from allowing seamen to disembark to shore on the islands, furthermore manning of the fleet was a constant administrative problem for Britain in the 1700s as pointed out by British Historian Richard Pares, this added a growing need to recruit skilled (free and/or enslaved) black mariners despite the objection of some commanders by the time of the seven years war, and by the late 1700s the widespread involvement of black West Indian employment in the maritime economy was less controversial than black soldiers in the army.

Jamaica and Antigua maintained dockyards for supplying, refitting and even building ships, work in these yards was usually undertaken by enslaved labour, additionally the dockyards themselves were constructed by many slaves as they “require[ed] the frequent Employ of Negroe Caulkers and Masons” as stated by Admiral William Hotham in a letter to Officers in 1779, in this same age of revolution, the Royal Navy as also became a desirable place of refugee for some runaway slaves to gain their freedom often by joining His Majesty’s naval service. One such example is during the American independence war as illustrated by professor Charles R. Foy’s in his paper “The Royal Navy’s Employment”: when Virginian officials’ observed in 1775 that many slaves who fled to British forces were “pilots and other maritime workers” or when, for instance, on 1 February 1777, Cornelius Cyrus and 34 other runaways came aboard HMS Brune in Virginia or, when, between 1775-77 HMS rose a twenty-gun frigate stationed at Newport under a naval Captain Wallace, saw black runaways regularly come on board. These runaways were characterised as “friend[s] of the Government” one such fugitive runaway was Tall Wheeler a 37 year old Guinea-born man who entered HMS Rose in November 1775 as a ‘friend’, then later became an Ordinary and an able bodied seaman, who in October 1779 died at sea, under employment on the frigate. No less than 25 black maritime fugitives, impressed seamen and volunteers served on the frigate (or 21.55%-26% of the entire crew). However there were no more than 5% of naval crews on the North American station that were identifiably black (or 10% accounting for the unidentified).

Interestingly, back In 1758, the Admiralty declined to hand William Stephens, an enslaved mariner from British Maryland who had voluntarily joined the royal navy, over to a slaveholder who claimed him as his property. That same year the Admiralty once again asserted that a former slave - William Castillo, employed as a naval seaman after fleeing from Portsmouth in 1756 for Royal Navy service, away from his master a Boston merchant captain since 1751, would not be re-claimed by his former master who he had since encountered on the streets of London only to be then unlawfully arrested, secured with an iron collar and boarded onto a ship, whilst being threatened to be sold into Barbados which prompted Castillo to write a plea letter meant for the admiralty to intercede on his behalf. That, resulted in the Admiralty deploying an Admiral Francis Holburne whilst instructing him “the Lords [of the admiralty] hope and expect whenever he [Holburne] discovers any attempt of this kind [to re-enslave other black sailors] he should prevent it”. Although Professor Maria Alessandra Bollettino notes in her PhD dissertation “as the Royal Navy impressed both enslaved and free men into service, many black men had little say in the matter”. For instance in one event occurring between 1753-62 involving HMS Northumberland, the loss of “thirty of her best Seamen by a Malignant Fever” with “a much greater number at the Hospital,” resulted in an Admiral Alexander Colvill impressing several enslaved men. Furthermore the Admiralty’s desire to keep slaves off the decks of its ships sometimes led it to order naval officers to discharge slaves to their ‘proper’ masters such is the case when Admiral Lord George Brydges Rodney learned “there is a Negro on board His Majesty’s Ship under your Command the Property of Lieutenant Wallace” and then ordered naval Captain William McCleverty an ulster Irish sailor of the Norwich, to “discharge the said Negro to his proper Master”, on the 23 February 1762.

However as mentioned in the dissertation of historian Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Manning either a British privateer or naval vessel exposed sailors of African descent to capture if their ship fell into the hands of their foes. Whereas white sailors were either exchanged for other prisoners of war, ransomed, or simply dropped off at the nearest port, most European ship captains regarded black men, whether enslaved or free, as property and thus potentially as booty if they were on board a vessel taken as a prize such as in 1760, when naval Captain James Lilley sent the Saint Jacques, a French privateer “laden with Sugars & some Indigo,” to a New York Admiralty court to be assessed following its surrender to HMS Duke of Cumberland. But the Saint Jacques sailed to New York without one of its crew members as Captain James Lilley retained on board and soon sold to a Spanish ship captain “the Negro Boy we took in the Polacca for 50£ York currency.” Hence even naval captains could be seen to deem any man of African descent who could not prove his freedom, a slave. Black seamen, no matter their true legal status, were often summarily sold by their captors.

During the 1720s-30s, Africans were sent to Navy Island just off the Jamaican

town of Port Antonio to establish it as a naval base on the north coast. Those

slaves were supplied with meat on a regular basis and were encouraged to

form families: Admiral Stewart commanding at Jamaica, despite having no

qualms about using enslaved labour, made a conscious effort to distinguish

between slaves on naval property and plantation slaves. Later, in Antigua in

1800, John Duckworth included £50 for the ‘King’s Negroe artificers encourage-

ment to industry’ in 1729. In addition to the use of King’s Negroes and slaves owned by the British crown, dockyard officials often had to hire slaves from local planters to quickly return naval vessels to sea. Albeit white naval seamen were not always friendly towards black Antiguans. naval Lieutenant Delasons “caused a Negroe Woman to be driven throughout the Yard tarred and feathered, with her Clothes tied up round her Breast, so that her Body, below was perfectly naked, which situation ... [caused] the taking off the Artificers Attention from their Duty, and violating the Good Order of the Yard”.

In the detailed paper of Professor Foy explains: The Black Mariner Database (BMD) demonstrates the commonplace presence of blacks in the Atlantic and in the Royal Navy. The BMD contains information on more than 1300 black Royal Navy seamen, Black maritime workers, including skilled artisans such as shipwrights and ship carpenters, were commonplace in the western Atlantic. They worked in ports from Boston to Cartagena and were critical to Britain’s and its European enemies’ abilities to operate in the Americas yet despite the considerable numbers of black ship carpenters in northern ports there is not a single black ship carpenter among the 1300 identified black naval crew in the BMD. Whats more black seamen faced racial discrimination in pay, treatment and in promotion in the Royal Navy as evidenced by naval pension records, pay rates and Royal dockyard employment statistics. For instance there were considerable numbers of black seamen and maritime workers in the British Isles, Historian Kathleen Chater found that ‘most black people’ migrating to Georgian England entered as domestic servants or as sailors and blacks were “strong[ly] represented” among British seafarers. Dr Norma Myers review of the Proceedings of the Old Bailey and Newgate Calendars indicates that 26% of black males whose occupation was noted were seaman and ‘about half’ of those who following the American Revolution, received benefits from London’s Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor had sea experience. Yet few of the many experience black seamen were actually employed In the royal dockyards of the United Kingdom, which were large industrial enterprises such that In the 1770s their total work force exceeded eight thousand, making them the largest employer in the British Empire and the backbone of British imperial power. A review of Portsmouth pay records discloses there were only a handful of blacks among the more than 2000 workers in the yard during the American Revolution, despite growing demand at the time. With regards to naval pensions, despite John Thurston’s drawing of a black Royal Greenwich Hospital pensioner along the Georgian Thames, black seamen receiving a pension were exceptional, there were only two such cases noted - this unnamed painted pensioner and Briton Hammond, an American black seaman who wrote of receiving a pension from the hospital.

This is further supported by the fact that Blacks are conspicuously absent from pension registers e.g. there is not a single identifiable black among the Chatham Chest’s 3320 pension entries for 1780. As prominent historian Mary Beth Norton has observed, black applicants seeking compensation for service during the American war faced scepticism on the part of British officials who often believed there were ‘Suspicious Circumstances’ behind blacks’ pension applications. Those that were granted pensions had to demonstrate extraordinary service like Shadrack Furman, a free black Virginian who worked for the British as a provisioner and guide, captured by American rebel troops to be given 500 lashes, blinded and rendered mentally deranged by an axe blow to the head. And to receive pension benefits a seaman had to submit an application in London, but most British black seamen resided in the western Atlantic and were rarely able to travel and/or cover the cost of travel to London to claim their benefits, hence blacks with naval service were largely excluded from Greenwich and Chatham Chest benefits between 1749 to 1763 only 4 out of 3002 Greenwich pensioners were from the Americas. contrastingly, Britain’s dockyards and naval operations in New York, Antigua and Senegambia demonstrates that black maritime workers were employed in all three, albeit in each of these regions blacks were treated differently than whites for instance, Rear Admiral Charles Stewart noted in 1731 that blacks in the Port Antonio naval yard “complain that allowances is too small”.

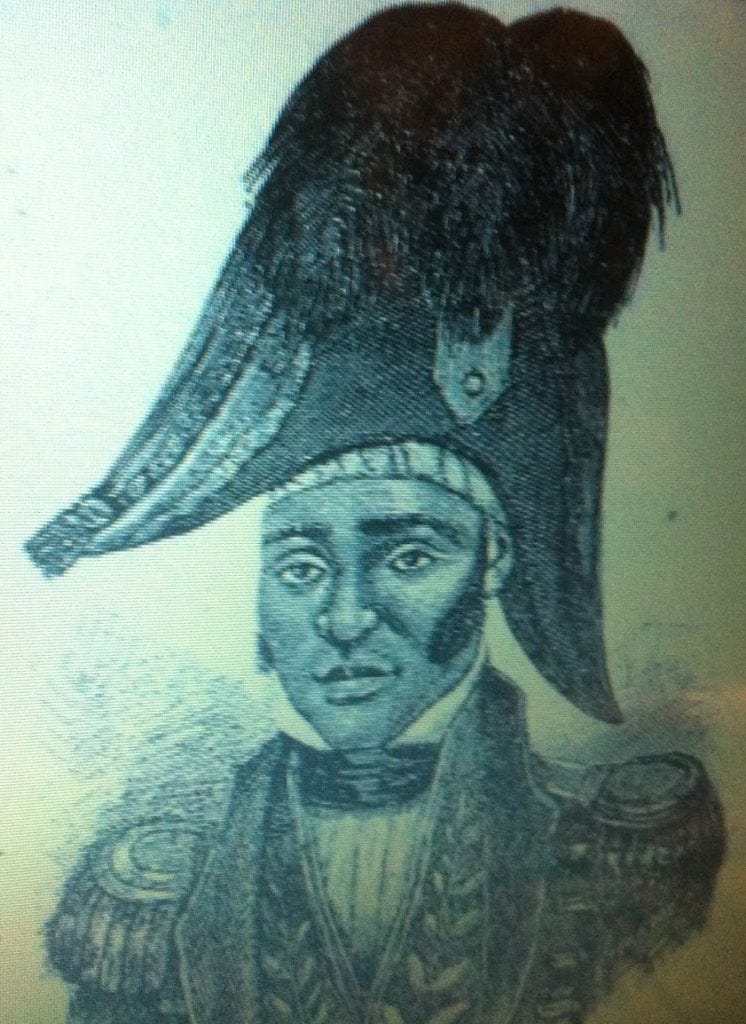

Captain John Perkins: ‘A Most enterprising Officer’ by Prof. Douglas Hamilton

Black mariners were entirely excluded from the officer corps of the Royal Navy, the only exception was a black Jamaican Officer named John Perkins, born in the Parish of Clarendon, Jamaica, to an enslaved woman in 1750 or thereabouts, after which, he was sent to Kingston and Port Royal as a child, where he became a ‘servant’ to a white Ship carpenter - William Young, who took Perkins into the naval service. On 22 June 1759, Perkins joined the Grenado, a bomb vessel, as Young’s enslaved servant, along with another boy, John Middleton. Both remained with their master when Young transferred to the larger Boreas on 7 March 1760. Perkins was not the only black boy aboard: the muster book records five other servants who joined at the same time. They were joined in June by two more: Thomas Bacchus and John Othello. On the Boreas, Perkins witnessed the capture of Martinique in 1762 alongside the siege and

capture of Havana later that year in the Seven Years’ war, After which Perkins later left Young’s service and began work as a naval pilot, becoming sufficiently adept to secure employment in the navy when aboard HMS Achilles. On 9 December 1771 he ran the Achilles ashore coming into Port Royal. He was blamed for the incident when Admiral Lord Rodney put the incident as having been caused ‘thro’ the unskilfullness of the pilot’. Perkins was subsequently court martialled two weeks later.

Found guilty, Perkins was thereafter “rendered incapable of servg. as Pilot in

any of His Majtys Ships” The verdict was enforced for a number of years

and he returned to life as a civilian pilot, but as his knowledge of the seas

around Jamaica increased, his expertise took precedence over the court’s

ruling. He re-emerged in the Admiralty’s muster books as one of the naval pilots in

HMS Antelope, then Rear Admiral Clark Gayton’s flagship on the Jamaica station in

late November 1775. In 1778, he secured his first command, on the private

schooner Punch in 1778, and he continued as a civilian to provide information

and intelligence to the navy, particularly in relation to French shipping off Saint

Domingue, he was nicknamed ‘Jack Punch’. He entered the navy’s pay as a lieutenant in the sloop Endeavour in 1781, at the turn of 1782, the Endeavour sailed towards Port Royal with two prize ships in tow when it was surrounded by French ships. Perkins escaped ‘by dint of good sailing’. In newspaper reports, Perkins was represented as an accomplished British naval officer, not as a black mariner. The prisoners on Perkins’ prizes reported a significant mustering of French and Spanish ships of the line, which corroborated other news leaking out from Saint Domingue, confirming British fears about an assault on their Jamaican possession, hence, equipped with this military intelligence, when the French fleet sailed to meet the Spanish in April 1782 the Royal Navy was prepared, and Admiral Rodney’s fleet intercepted and defeated them at the Battle of the Saints.

Despite his earlier misgivings, Rodney was so impressed that he promoted Perkins for his “behaviour in taking the French sloop with so many Officers on board her, and by your many services to His Majesty and the Publick”. The Endeavour was re-established as a naval sloop of war with 12 guns and was renowned for “the superiority of her sailing to everything in these seas”. Rodney wrote to Perkins: “[I] hope you will have an opportunity of exerting yourself in the Service of your King & Country with as much applause now you are her Captain, as when you was only her Lieutenant and Commander”. At the end of the American war, the Endeavour was decommissioned and sold off, and Perkins was placed on half pay. He spent most of his time in Jamaica but travelled to Britain, first in 1784 and then in 1786. On neither occasion did he

enjoy the experience of the British climate: “I could not bear it”, he wrote, “I felt the cold to such afect [sic] that I was obliged to quit England in the month of October, and

beleve [sic] it would have been the death of me had I not left”. By this time

Perkins had had nine children (at least 6 of whom survived) with three different

women, one of whom was likely to be his wife.

A few months after the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in May 1791, Lieutenant John Perkins, on half pay, was arrested by French authorities in Saint Domingue and “confined in a dungeon … under the pretext of his having supplied the people of colour with arms”. His arrest promoted a vigorous response from the Royal Navy, and two ships – HMS Diana and HMS Ferret – entered Jérémie harbour in south-west Saint Domingue to negotiate his release. naval Captain Thomas Russell of the Diana argued there was no evidence for the French accusations of collusion with the Haitian slave rebels. Instead, Russell believed – somewhat implausibly – that Perkins was being held in revenge for his actions off Saint Domingue during the American War of Independence in 82, which had ended nearly a decade earlier. Despite receiving formal requests from the governor and naval commander at Jamaica, the French refused to budge, informing the British that the “Law imperiously commands us to retain Mr Perkins”. Unofficially, Russell was told by the French president of the Council of Commons at Jéremié that Perkins would be executed. After more than a week of fruitless diplomacy and with time of the essence, Russell anchored off shore

and dispatched the Ferret under then British Captain William Nowell to intercede With Perkins just hours from first the rack then the noose, Nowell demanded his immediate release on 24 February 1792, telling French officials that failure to do so would “draw down a destruction you are little aware of”. In the face of British aggression, the French acquiesced and released Perkins who was taken back to the

Ferret and then transferred to the Diana at sea, thereby averting an international incident of Britain declaring war on France there and then with the attack of their colony to save Perkins in February of 92. The fact that the kingdom of Great Britain was prepared to declare war on France over Perkins - a senior black officer in the Royal Navy that wasn’t even there to conduct official business - and when Britain was not yet at war with the French until 01 February 1793 - a year later, raises interesting unavoidable questions about Perkins’ place in the late 18th century multi-polar world of European colonial powers.

Perkins remained available to the navy in a more or less unofficial capacity throughout the decade of peace between the American and French wars. There was great British concern about the slave rising in Saint Domingue not least in case ‘the contagion’ of revolt should spread to Jamaica little more than 100 miles to the west. In November 1791, the Committee of West India Planters and Merchants in London had persuaded the government to increase its military presence in Jamaica because “attempts have been made and are still making to create and ferment in the minds of the Negroes in our Colonies a dangerous spirit of Innovation”. British officials in Jamaica, wanted intelligence that can offer more than one perspective on events in Saint Domingue. To secure it, they turned to the Royal Navy and to John Perkins. Even though the British government’s public utterances declared support for the French plantation owners and concerns about the slave revolt, a series of accusations were made that the British maintained connections to the slave rebels.

Perkins was more than just a spy though. The French authorities had detained him “for his connexion with, and services to, the rebellious negroes”, including supplying them with arms and ammunition and “instigating them to rebellion, in order to

effect their emancipation or liberty”. If true, Perkins adopted (or was placed

in) a position diametrically opposed to the general view of the Jamaican elite

and the official policy of the British government. Given the scale of the effort to get

him back, it seems unlikely that he was there in a purely private capacity, It is

probable that he was there under official instruction. Moreover, the British did not send just any naval lieutenant on half pay to gather information in Saint Domingue; they sent their officer with the greatest knowledge of the seas in the area, a fluent

French speaker and their only black officer, that is, the only one who

could more easily assimilate with the insurgent groups rather than with the

white population. Commodore John Ford, commanding the Jamaica station, wrote to the Admiralty in March 1793 praising Perkins as ‘a most active, enterprising, useful officer, who might be employed here in a small vessel with great advantage to the State, provided … there arises an occasion for his Services’. A month later, and before he could possibly have had a response from London, Ford reported that he had given Perkins command of a newly purchased schooner called the Spitfire, which was ‘a very fast sailer’.

His specific role similar to the American war, was “to gain Intelligence of the Enemy’s Force and Movements at Port-au-Prince and Cape Francois [sic]”. Most of the rest of

Perkins’ naval career was focused on Saint Domingue and the waters around it

and he became the navy’s most experienced officer in those seas. Newly restored

to his official naval role, Perkins quickly attracted press coverage for his exploits.

In November 1793, for example, Reporters at The World in London reported that Perkins’ repeated escapes from the clutches of larger French vessels. was then promoted to a larger ship, the captured French prize Marie

Antoinette, as “an officer of zeal, vigilance and activity” as it was reported in the

London press. None of his press coverage yet made any reference to the colour of

his skin: he remained in the public mind an example of a brave, manly and

white British naval officer. The Marie Antoinette was part of the squadron

led by Ford that took Port-au-Prince in June 1794 before Perkins was finally promoted to the 14-gun man-of-war Drake in 1797 as a Post Commander after Admiral Rodney had repeatedly failed to get Perkins promoted beyond lieutenant due to racial prejudice & Perkins illiteracy as a former slave. He was promoted naval post-captain in September 1800 and appointed to the 24-gun Arab with 155 men. The BMD does not evidence another single black mariner obtaining the rank of post captain and only two who were midshipmen, that we will discuss later.

Back In June and July of 1782, one of his first tasks as lieutenant was to support the manning of the Jamaica squadron by the impressment of sailors. Impressment had long been a matter of great controversy, not only had the American Declaration of

Independence explicitly listed it among ‘the long train of abuses and usurpa-

tions’ perpetrated by George III, but it had also been the subject of significant

periodical debate in Britain and America. Much of the language used to decry

impressment in Britain described it as a violation of liberty and a “most

absurd and cruel tyranny towards the most meritorious branch of the community”. In so doing, it aligned impressment with two distinct understandings of

‘slavery’ in Britain and its world: one was the result of arbitrary rule that brea-

ched the ‘unalienable’ rights of free men and the other, particularly in the Amer-

icas, meant the enslavement of Africans. The Royal Navy relied on the

impressment of mariners, just as impressment further complicated

the relationship of the navy to ideas of slavery, therefore, so too did Perkins –

the black Jamaican – whose official position cast him in the role of the black

coercer of white sailors and free men, and as the commander of his ship, Perkins was responsible for determining punishments for offences not serious enough for court martial. Under the Articles of War, naval captains could impose a punishment of up to 12 lashes, although this was often taken as meaning for each offence, and punishments of multiples of 12 were common. For more serious offences, courts martial were convened and dealt with matters of theft, desertion, mutiny, violence and refusal to follow orders. The courts martial had the power to impose capital punishment and corporal punishments of up to 1000 lashes. Naval punishments, therefore, for all the legitimacy vested in the courts martial at times looked less brutal than those carried out to the enslaved.

In just over a year in command of the Drake, Perkins sentenced 14 of the 86

sailors to punishments of between 7 and 18 lashes. In the Arab he punished 11 men, including 2 masters, in eight months, mainly by whipping. One of the masters, James Tims, deserted along with five other men while the ship was at

Martinique. This did not make Perkins the most violent captain in the squadron, and there are recorded instances of far greater brutality, but neither was

he unwilling to use the lash as a black naval captain onto white sailors found guilty of breaching the rules. For the first time however, Perkins appears to have struggled against directly racialised disobedience. In May 1803, he wrote to his patron John Markham at the Admiralty to complain that aboard the Tartar, his lieutenants were too young, and that the first lieutenant ‘is not more than 21 or 22 no sea man, & will never make an officer as long as he lives”. This is likely to be the same officer – a “smart and proud Englishman” – whom Peter Chazotte reported as saying it was “a cursed disgrace for us British officers to be placed under the command of a blood-thirsty colored captain”. Chazotte also described Perkins as “an epauletted scoundrel” that acted as a “regular agent of the Wilberforce Society”.

In 1803, Perkins spent a great deal of time cruising the waters off Hispaniola in

the Tartar and took part in the blockade of Saint Domingue, which was partly an

attempt to ensure that economic damage was inflicted on France, and partly to

ensure that the revolution and the revolutionaries were confined and kept away

from the British colonial islands. When the UK attempted to mend commerce & trade relationships with Haiti immediately after the revolution, they sent their diplomat, a British envoy named Edward Corbet escorted by Perkins on the Tartar, to meet & negotiate with General Dessalines at Saint Domingue, there was more than one back and forth trip that occurred however these negotiations were unsuccessful in part due to the deep distrust Haitians’ had for British intentions. During these journeys to Port-au-Prince in February and March 1804, it was discovered that Perkins cargo on the Tartar consisted of a huge amount of guns that he sold to Haitians. When Corbet was made aware of this in the second voyage he wrote to Perkins:

“I cannot but consider the selling to, & supplying those People [Haitians] with Arms, which may ere long be turned against the Island of Jamaica or the British Commerce, to be impolitic & improper in the extreme, & as such I now make my Solemn Protest against it”

Corbet made his opposition known, in equally clear terms, to the Lieutenant-governor George Nugent in Jamaica, who had been unaware of the transactions, which amounted to around 5000 weapons including ‘musquets, carbines & swivels’. He seemed not to know that Perkins had already shipped 1800 weapons on the first trip.

These concerns were relayed to Perkins’ commander, Admiral Duckworth,

and perhaps reflect some mistrust of the black officer. Duckworth, however, vouched for Perkins, writing to Evan Nepean at the Admiralty to say “if I don’t comment on it, I consider the Transaction if not explained might operate against the Reputation of Captain Perkins with His Majesty’s Ministers”. Duckworth went on to explain that these were part of the prize weapons & French ships that had been seized by the Royal Navy during the French capitulation at the end of November 1803 at Cap Français, which had been enabled by British naval blockade of Saint Domingue. It aided the rebel cause to such an extent that the British were allowed by Dessalines to occupy the naval bases at Saint Nicholas Mole and Tiburon. Those French ships were auctioned in Jamaica, but the weapons were sold back to Dessalines in Haiti. Duckworth claimed the guns would have been returned sooner had Dessalines not wished to keep British forces out of disputes in pre-independence Haiti.

With independence and Corbet’s mission, Duckworth explained - “I thought it my Duty to direct Captain Perkins to carry up 1800 [guns] which General

Dessalines received with great courtesy, paying his own Price, and requested Captain

Perkins to bring the remainder, which I directed him to do on his second visit”

In other words, as far as Duckworth was concerned this was an entirely legiti-

mate sale of French prize weapons to Haiti and he further justified it by saying “Captain Perkins being directed to promote the object he might point out

as being beneficial to the negotiations”. Perkins, once a ship carpenter’s enslaved servant now found himself at the heart of Foreign Office & Naval diplomacy between Britain and Haiti in the immediate aftermath of independence and had came into contact with commander of the Jérémie district of Port-au-Prince, General Laurent Férou a later a signatory of the Haitian constitution and with Dessalines alongside the Jamaican governor, with whom Perkins “had much business”.

The trade negotiations were ultimately unsuccessful after the British took

fright when Dessalines ordered the slaughter of the remaining white French

inhabitants of Haiti in March 1804. Some of the news about the massacres

came from Perkins, who warned Duckworth of their imminence when he

returned to Port Royal at the beginning of March. Duckworth ordered

Perkins to “call at the various Ports where the General [Dessalines] was likely

to be” and “to, use his Influence for the preservation of those poor unfortunate creatures [white French]”. Duckworth clearly felt that Perkins had developed a sufficiently useful relationship with Dessalines to have some influence. Alas it was to no avail and Dessalines embarked on a massacre of the white plantation owner population. Perkins was one of the first British officials to see the aftermath of the massacres and he described them in detail in letters to Admiral Duckworth. In

March and April 1804, Perkins reported the rape and massacre of white

planters across the country: “such scenes of Cruelty & devastation have been committed it is impossible to imagine or my Pen to describe”. Perkins believed that few of 450 people in Jérémie had survived and that 800 whites were killed in Port-au-

Prince in eight days, his version is largely consistent with that of the racist English officer Chazotte who was one of the few survivors. The carnage was on such a scale that Chazotte, usually having Perkins as the sole object of his racist ire, wrote “even that cold-blooded agent of Wilberforce [was] horror struck by the abominable deeds of brutish lust, carnage and pillage”. Perkins was ordered to help evacuate survivors, including some Spanish settlers close to the border between Haiti and Santo Domingo in Mancenille Bay on the north coast.

Perkins’ complex relationship with slavery – and to his place in Caribbean

society – went one step further. Not only was he a naval officer, he was also a

land and slave owner and it was to this occupation that he most likely turned

after 1805. He was reputed to have been involved in the capture of 315 prizes

and 3000 prisoners over the course of his naval career, and it is probable that

he used a certain portion of his prize money to acquire property in Jamaica. This was not an uncommon practice for naval officers, of the 41 commanding

officers in the region in this period at least nine of them bought or inherited

plantations, or acquired them through marriage. Officers of lower rank also

bought estates or married into the slave plantation owning class, the most notable being the young Horatio Nelson, who married Fanny Nesbit of Nevis. The Jamaica Almanacs for 1811 and 1812 record Perkins as owning the Mount Dorothy

estate in Saint Andrews parish, along with, respectively, 23 and 26 slaves, as a

black plantation owner, he was not entirely unique, but his status was predicated on

his naval rank and career. After his death in 1812, his estates passed to his children, Only one of his slaves was manumitted by his will – and by a codicil

attached to it – a mulatto slave named John.

Limitation of Black Mariners in the Navy

In a random sampling of 556 officers who passed the lieutenant’s examination from 1775 to 1805, Naval Historian Evan Wilson found that 2% were of white working-class background. Had a similar percentage of blacks passed the lieutenants’ exam or been junior officers, one would find twenty-six black officers in the BMD, rather than the seven that one finds. Even though those from working-class backgrounds were promoted to post captain at a rate only 65% that of all officers, considerable numbers of working-class white seamen did move up the naval hierarchy. In contrast, Perkins, Barlow Fielding, three Senegalese junior officers and two midshipmen are the only examples of identified black naval officers and none were commissioned after taking the lieutenant’s exam. Barlow Fielding serves as a good example that limits for black sailors in the Royal Navy were not solely due to illiteracy or lack of navigational skills. Fielding was a boatswain on HMS Orepheus off the Kent coast. In 1780 he requested a transfer, naval Captain John Colpoys explained the request was due to the ship’s crew having “taken a Dislike to the man’s Colour”. Colpoys further believed it was “very difficult, and even impossible ... for me to remove a Particular Prejudice” among the ship’s crew. Instead of the requested transfer two months later Fielding entered Haslar Hospital.